As sonographers, we have all commonly experienced the patient presenting with shortness of breath and unable to lay down flat for their echocardiogram. As we begin to scan the patient, we immediately visualize a large amount of fluid around the heart. Keeping our poker faces on point, we take charge of the situation and complete a thorough evaluation of the severity and degree of pericardial effusion, ruling out the presence or absence of tamponade. It is not often we are presented with a life-threatening condition, but when we are- we should be able to confidently evaluate the condition and provide the essential information to the physician.

The pericardium contains both a fibrous sac and serous membrane. The fibrous sac attaches to the great vessels, sternum and spine. The pericardial layers include:

A normal pericardium is <2 mm in thickness.

In a normal average-sized human, the pericardial space contains around 20-60 mL of fluid. The fluid is composed of ultrafiltration of plasma and is drained by the lymphatic system. It acts as a stretchy elastic lubricated sac, serving various functions (including but not limited to):

Let’s cover basic hemodynamics of the pericardium. Normal pericardial pressure is low. It follows the change in intrapleural pressure (pleural = lung cavity) and right atrial pressure, therefore being influenced by respiration. The change in pressure facilitates the pooling and filling of blood to the right heart.

The pericardium can easily accommodate a small amount of excess fluid (up to 250 mL) before pericardial pressures begin to rise.

Think of a balloon that is 3/4 full of air. The balloon represents the pericardium. With it being 3/4th full of air, we can apply pressure and compress it to a degree and when released, it returns to expanded state.

A pericardial effusion occurs is when an unfavorable amount of fluid collects within the pericardium, increasing the pericardial pressures. The increase in pericardial pressures can cause harmful effects on the heart:

There are many etiologies to the development of a pericardial effusion, ranging from infection, trauma, inflammation, cancer/radiation and idiopathic.

This my friends, is the extreme case of a pericardial effusion! Think… LIFE-THREATENING EMERGENT SITUATION!

Cardiac tamponade is a condition that causes impaired cardiac filling due to a high pericardial pressure and increased amount of fluid within sac. In other words, the heart is being compressed, squished! The diagnosis of tamponade is based on a spectrum of hemodynamic abnormalities!

Refer back to our balloon analogy- if we were to fill that balloon with the maximum amount of air it can hold, we wouldn’t be able to squeeze it… it would be stiff!

That is essentially what is happening with the pericardium. When there is a rapid increase of fluid and high pressure, the pericardium cannot stretch anymore to accommodate.

So what is happening?! During inspiration:

The degree of severity is based upon volume of fluid, rate of accumulation and compliance of pericardium.

Tamponade will be associated with a moderate to large pericardial effusion. However, tamponade can be present with a small or localized effusion in situations associated with dissection, trauma or post-procedural event.

The term ‘swinging heart’ is a great description of the appearance… literally the heart swinging in a pool of fluid. Imaging characteristics of tamponade can range from a variety of findings.

Echo is the primary screening tool to determine the presence, evaluate severity of fluid and hemodynamic state. Each lab should have a specific protocol in place for evaluation of pericardial effusion. The evaluation should include:

Let’s go into further details of how to evaluate each of these important screening tools.

The presence of pericardial effusion appears as an anechoic space between the epicardium and parietal pericardium. Normal or trivial pericardial fluid (<50 mL) can be visualized only during systole. When fluid is visualized throughout the cardiac cycle (systole & diastole), the physiologic amount exceeds >50 mL.

The accumulation of fluid can appear in various ways:

Effusions can contain loculated strains within the fluid filled space as well. These will appear stringy and hyperechoic.

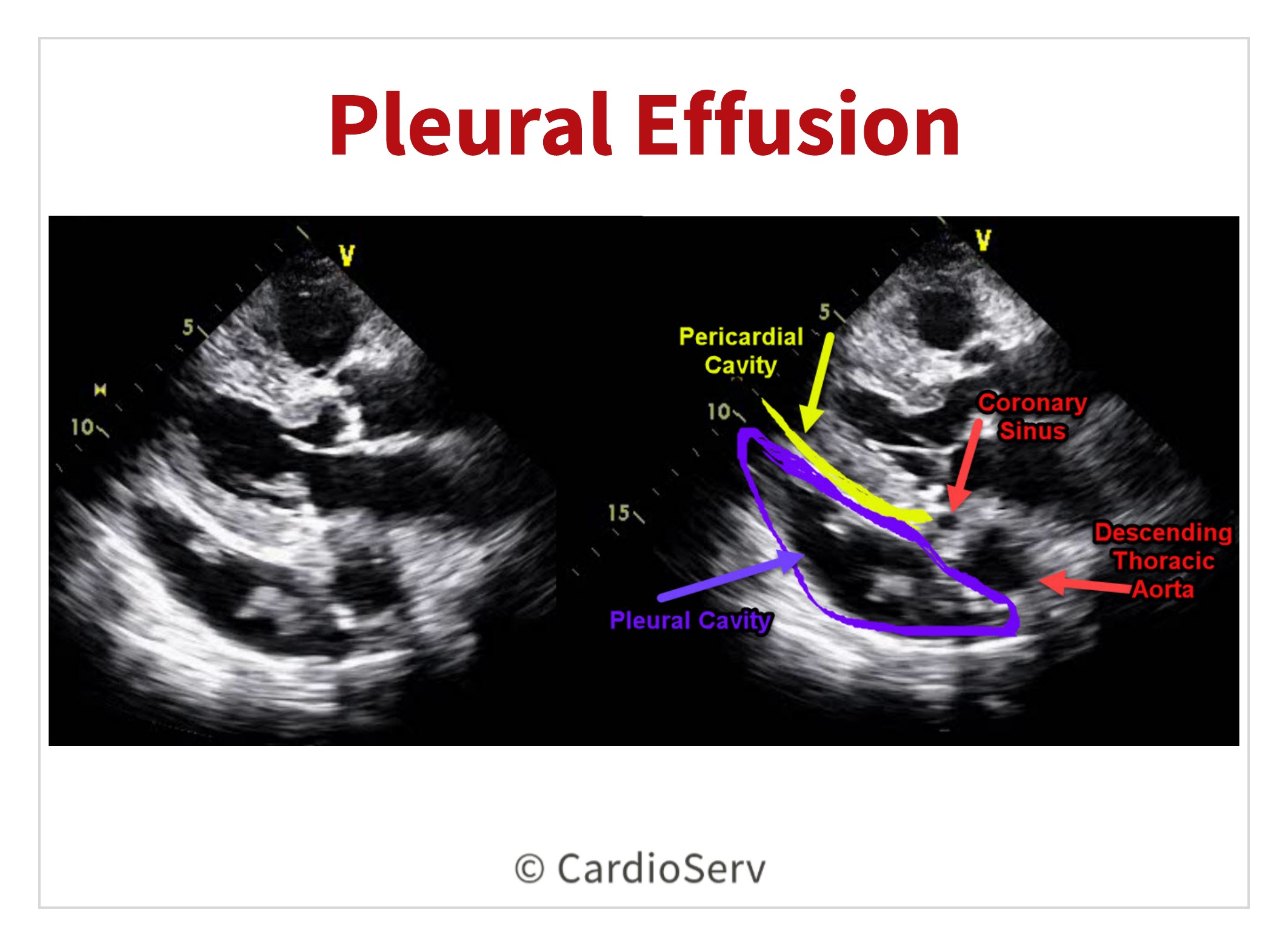

It is common to mistake a pleural effusion for a pericardial effusion. A pleural effusion is fluid located in the pleural (lung) cavity. A left pleural effusion can commonly be identified in the parasternal long axis view (PLAX).

In order to correctly identify the difference between a left pleural effusion and pericardial effusion, locate the descending thoracic aorta (DTA).

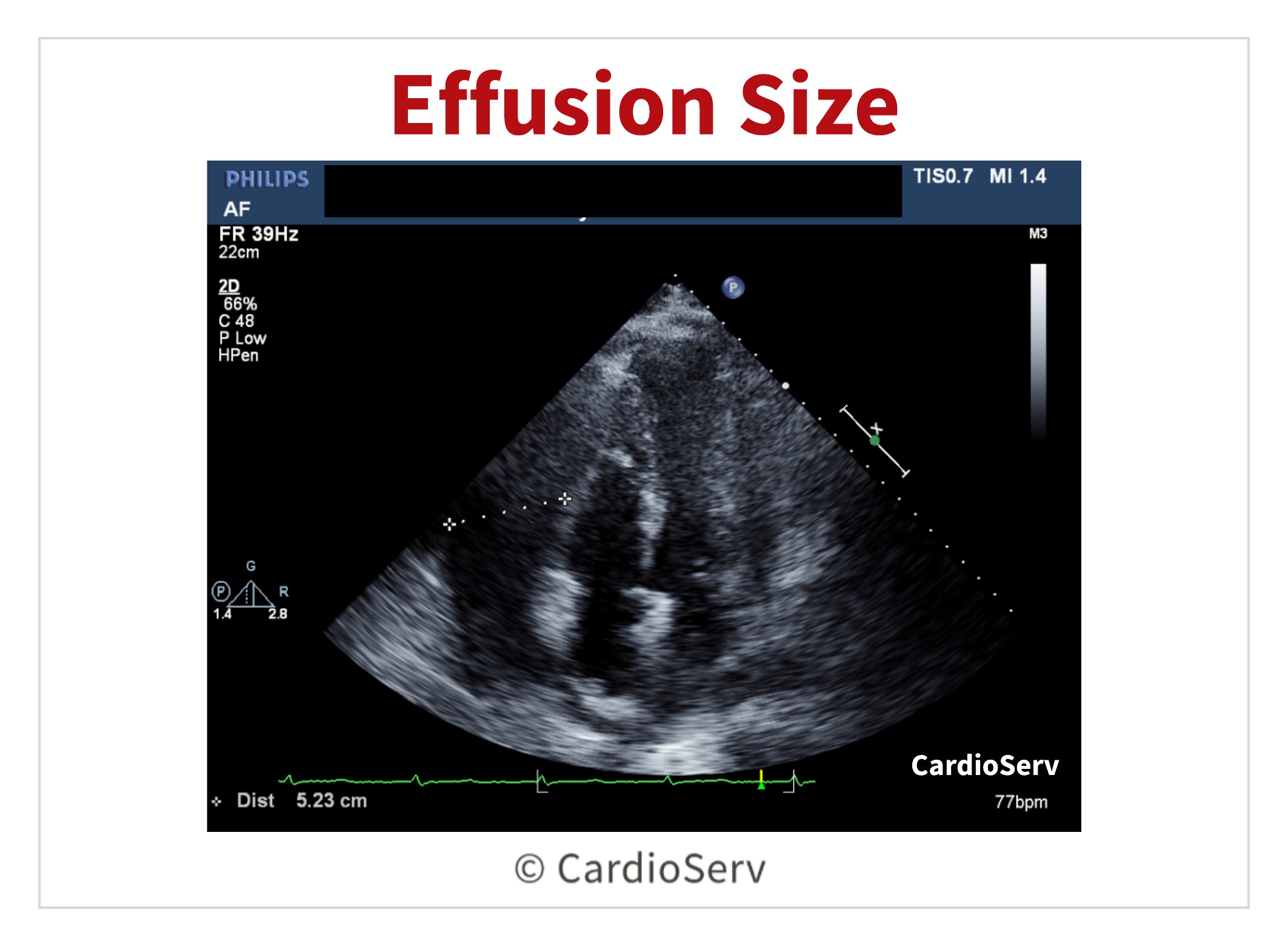

To measure the size of the pericardial effusion, a caliper is placed between the epicardium and parietal pericardium at end-diastole.

The largest pocket measured should be placed on echo report along with the distribution of fluid (circumferential or localized).

Chamber collapse will occur when the pericardial pressure exceeds the pressure in the chambers. It is common for the right heart to collapse first.

We can visually evaluate chamber collapse. Another way to evaluate this is by utilizing M-Mode and placing the cursor on the right ventricle. Turn the sweep speed to slow in order to visualize collapse during multiple cardiac cycles and respirations.

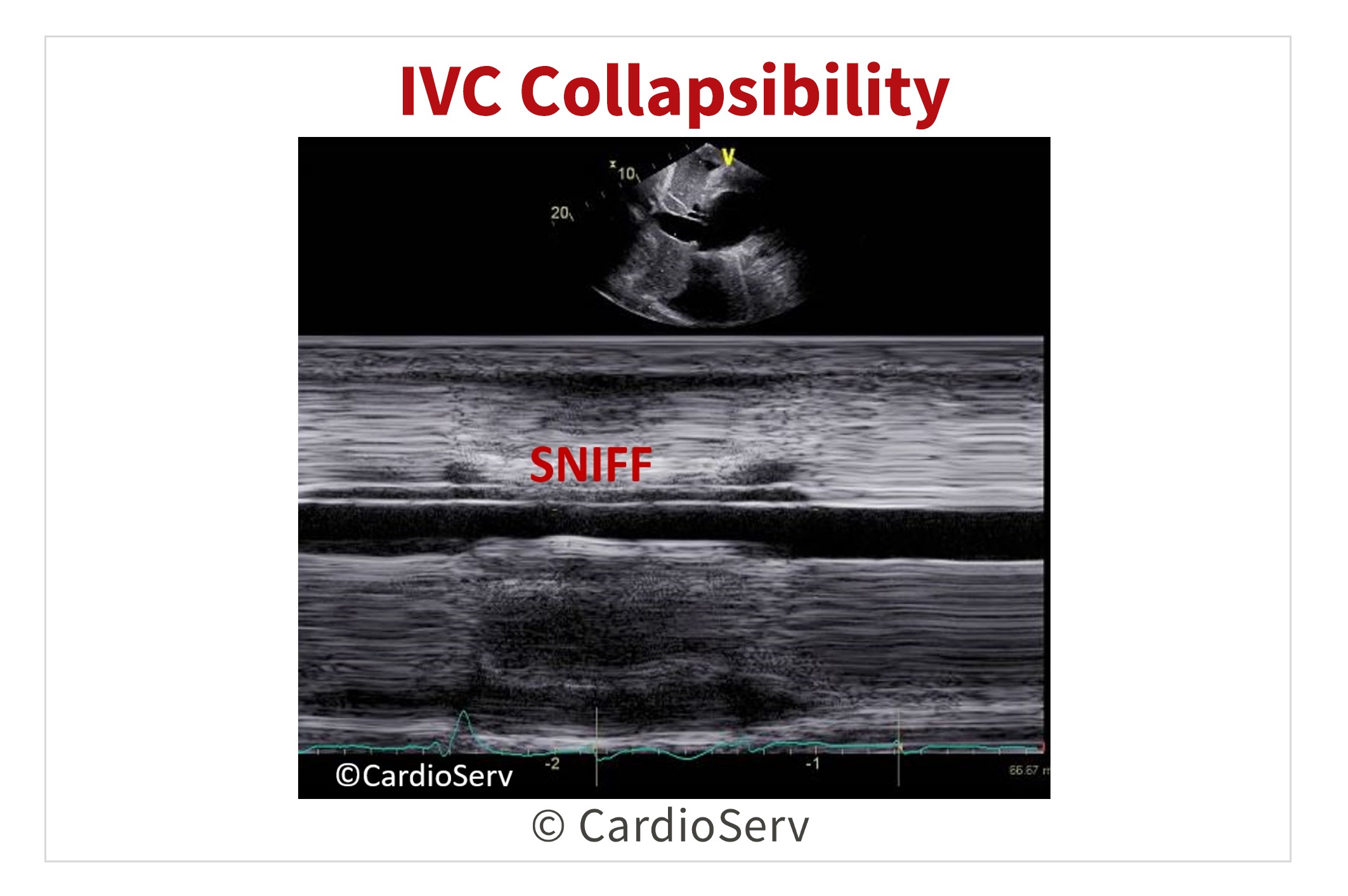

IVC evaluation is another key screening tool in the presence of tamponade. Refer back to our past blog HERE to read tips & techniques on how to properly evaluate the vessel.

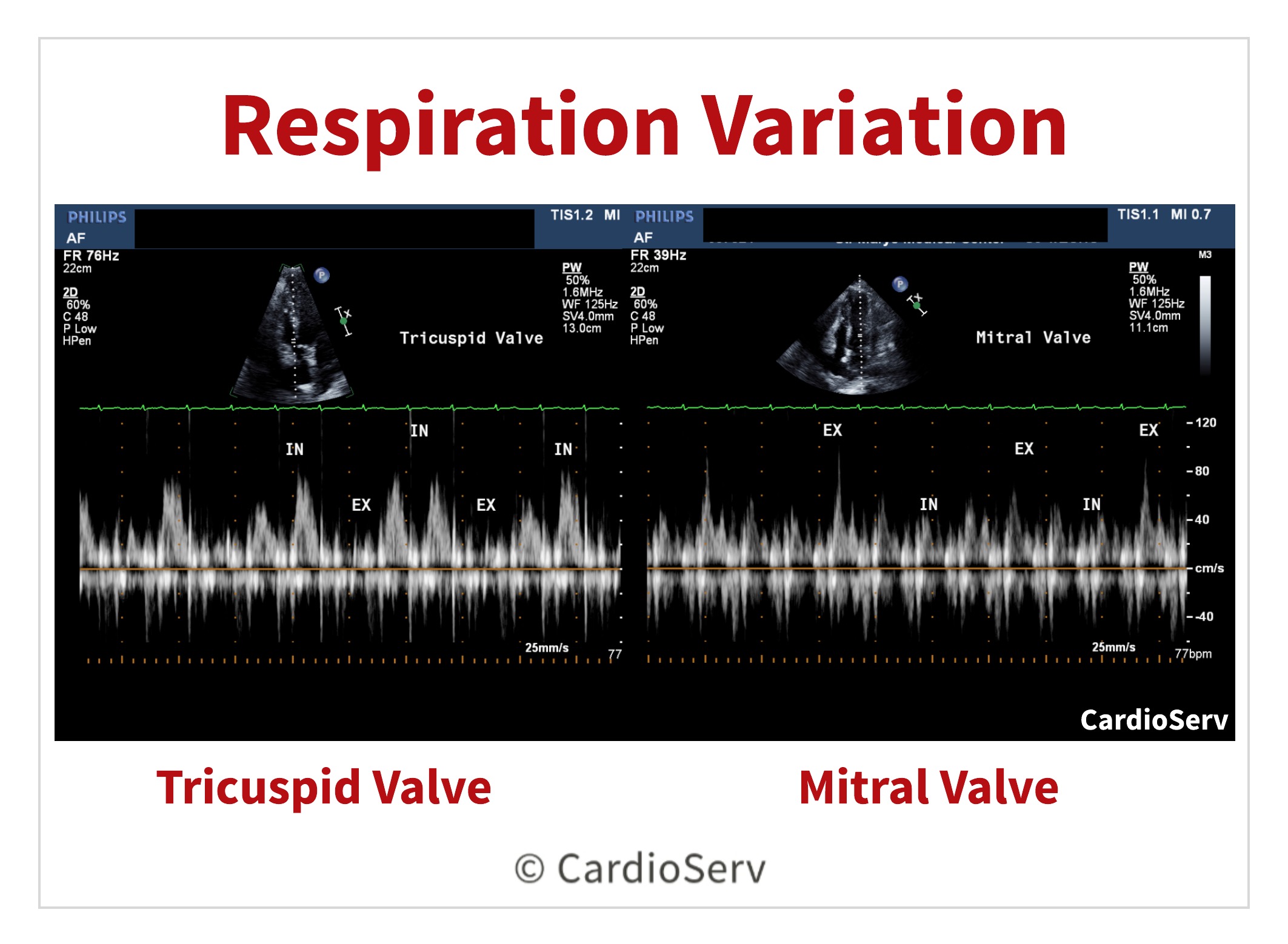

Since tamponade affects the filling pressures and amount of volume, there will be respiration variation. We will see this in both the shift in the interventricular septum (IVS) and with valvular peak inflow velocities.

Visualizing the shift of the IVS:

The peak filling velocities of the tricuspid and mitral valves will display respiration variation in the presence of tamponade. During inspiration, the right heart filling pressures will increase and decrease with expiration. To evaluate this change:

Evaluation is done to both the tricuspid and mitral valve. Let the Doppler waveform run for multiple breaths to display respiration changes.

The hepatic veins will also demonstrate respiration variation too. You can read our blog on how to Doppler them HERE.

Here are 6 clues to indicating the presence of cardiac tamponade:

Andrea Fields MHA, RDCS, Cardiac Clinical Director

Andrea Fields MHA, RDCS, Cardiac Clinical Director

References:

Otto, C. M. (2017). The practice of clinical echocardiography. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier.

Sep

2018

Sep

2018

Sep

2018

Sep

2018

Oct

2018

Jan

2019

Feb

2021