In the past weeks we had guest writer, Michael Owen, share how to assess diastolic dysfunction. He broke down the algorithm that ASE uses to evaluate the presence of dysfunction. The full ASE article is long and intense. Michael did a great job at simplifying the evaluation process. While featuring this Mastering Diastology series we started to receive a lot of questions. We realized that it would be helpful to take a step back and review the basics. All this great information regarding diastolic dysfunction means nothing to us unless we have a basic understanding of the topic and how it relates to our daily use. We are going to go back to the beginning. Let’s talk diastole!

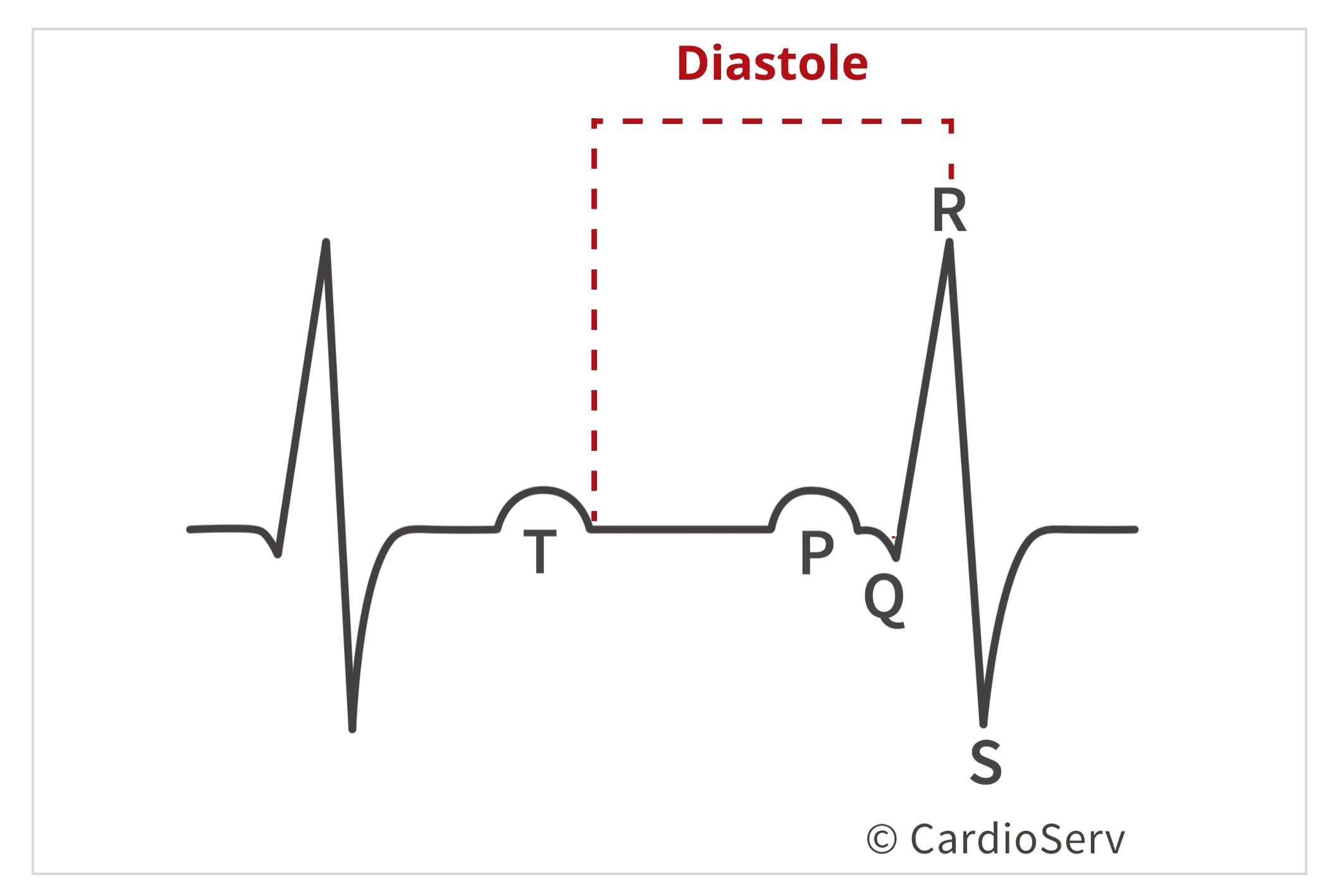

First, let’s discuss what is all involved in diastole. Diastole is the period of the cardiac cycle that involves filling of the ventricles. Looking an EKG, diastole begins after the T-wave and ends at the R-wave of QRS complex.

Diastole starts when the aortic valve closes and ends at mitral valve closure. There are four stages to diastole:

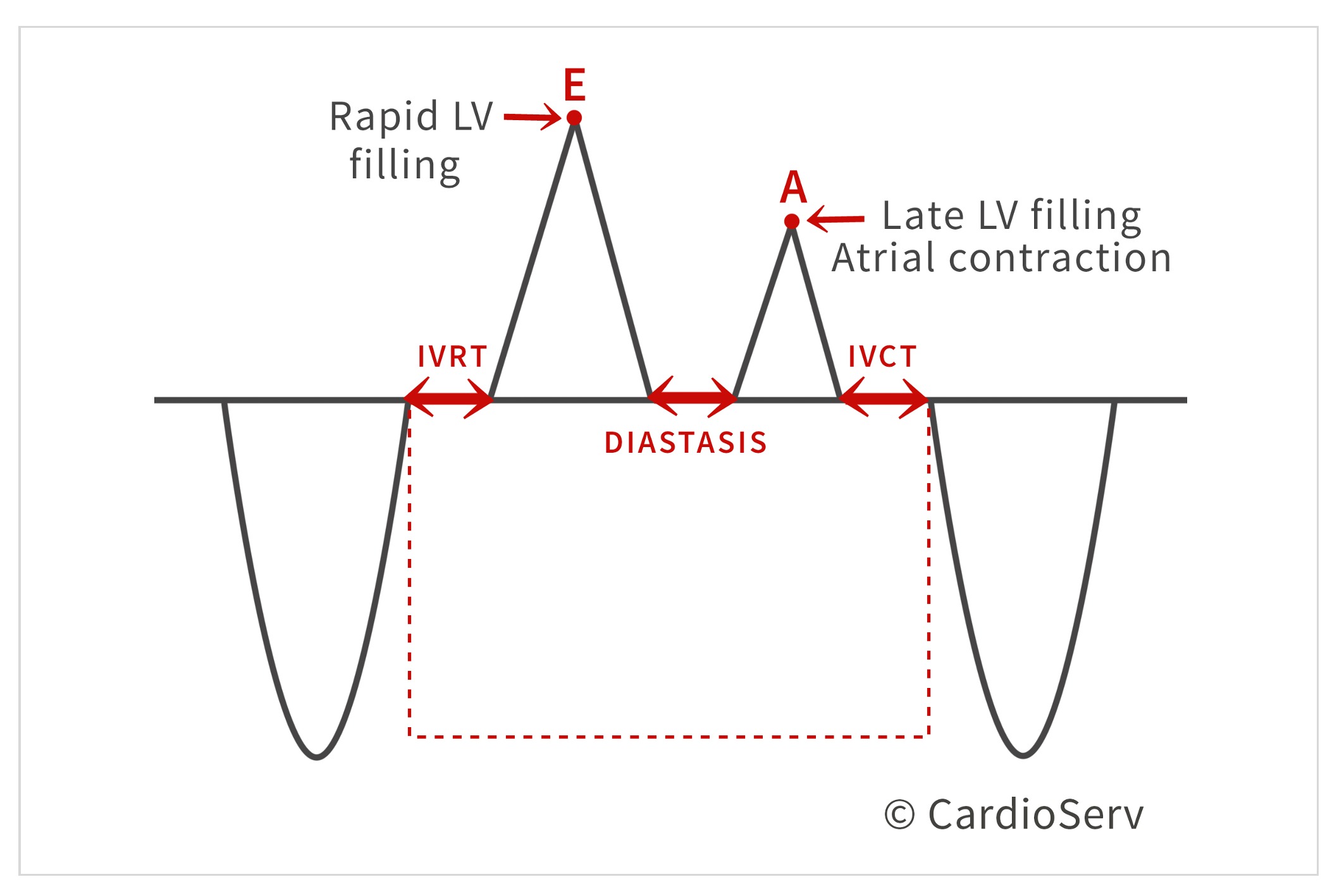

Isovolumic relaxation is a very small increment time when the aortic valve is closed, before the mitral valve opens.

The name explains what is occurring during this phase of diastole:

The ventricle drops in pressure to allow it to completely relax in preparation for filling. Since this is a small increment of time, when both valves are closed, the volume of the ventricle does not change. Once the pressure in the ventricle drops below the left atrial pressure (LAP), the mitral valve opens. This ends this stage of diastole and starts the rapid filling phase.

Once the pressure in the LV drops below the atrium, causing the mitral valve to open- rapid filling of the ventricle occurs, increasing the pressure and volume of the cavity. Once the rapid filling begins, the LAP and volume rapidly decreases as blood is pushed into ventricle, emptying out of the atrium. Around 80% of the blood is pulled into the ventricle during this time.

The heart rate determines the duration of the diastasis phase. As the LV pressure increases and LAP decreases due to rapid filling of the ventricle, the two pressures start to become equalized. Since most of the blood was pulled into the ventricle during the rapid filling phase, there is minimal blood left within atrium. Therefore, only a small amount of blood is moved to ventricle during this mid-diastolic phase.

The last phase of diastole is atrial contraction. The name explains what is occurring: the atrium contracts due to a small increase in LAP, which causes the remaining 20% of blood to be pushed into the ventricle. Once this occurs, the LV pressure is now higher than the LAP, which causes the mitral valve to close.

Understanding diastole is a key concept to have in order to evaluate diastolic function. By having an established knowledge on what is occurring during each stage of diastole, we can have a better understanding of the physiologic standpoint for determining diastolic function.

Andrea Fields MHA, RDCS

Andrea Fields MHA, RDCS

Stay Connected: LinkedIn, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram

References:

Nagueh, S. F., MD, Smiseth, O. A., MD, & Appleton, C. P., MD. (2016). Recommendations for the Evaluation of Left Ventricular Diastolic Function by Echocardiography: An Update from the American Society of Echocardiography and European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. American Society of Echocardiography, 29(4), 277-314. Retrieved October 31, 2017, from http://asecho.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/2016_LVDiastolicFunction.pdf

Anderson, B. (2017). Echocardiography: the normal examination and echocardiographic measurements. Australia: Echotext Pty Ltd.

Nov

2017

Nov

2017

Nov

2017

Nov

2017

Nov

2017

Nov

2017

Dec

2017

Dec

2017

Jan

2018

Apr

2018

Apr

2018