Last week we discussed how the physiological determinants of diastole play a role in the evaluation method of determining diastolic function. This week, let’s talk about how pathophysiological factors can alter the findings in the presence of diastolic dysfunction.

Let’s recall the hallmark signs of diastolic dysfunction:

When these hallmark signs are present, it is the hearts way of indicating a secondary response to compensate and maintain adequate LV filling and stroke volume.

When we evaluate for diastolic function, our goals are:

We are able to use a combination of echo specific indexes for evaluation:

We are going to break down each one of these into a series of blogs!

When we exam our patient using these parameters, we are obtaining information in regards to ventricular relaxation and estimating ventricular filling pressures. The ventricular relaxation and ventricular filling pressures involve both the active and passive processes of diastole.

During systole, the ventricle contracts allowing potential energy to be stored, in other terms ‘restoring forces’. When diastole begins, the stored energy is released allowing the ventricle to relax and fill properly. The active process of diastole is therefore the ventricle’s ability to relax and utilize restoring forces. There is a loss of restoring forces when the ventricle relaxation ability decreases, becoming more stiff.

The passive phase of diastole involves the ventricular filling pressures. The compliance or elasticity of the ventricle to allows the blood to fill the chamber adequately. This compliance is determined by the relationship between change in the LV volume and change in pressure during diastole, aka ‘pressure-volume relationship’. Invasively we could measure this via pulmonary catheter wedge pressure (PCWP). Non-invasively, via echo, we evaluate multiple parameters that give us insight to the mean left atrial pressure (LAP), which correlates best to PCWP.

Once diastole begins, potential energy is released that allows the ventricle to relax in order to fill adequately. When the ventricle reaches this state, the next phase of rapid filling begins. This process generates a pressure gradient (PG) from the left atrium (LA) through the transmitral annulus, towards the left ventricle (LV) apex. The PG across the annulus produces the transmitral flow velocities displayed on our screens. The waveforms are influenced by the ability of the ventricle to relax and the compliance of the LA to generate a PG to allow rapid filling.

We are unable to measure the exact rate of ventricular relaxation, but can have suggestive measures that help us conclude if the rate is impaired/prolonged or shortened. We can also acquire indicative information of the LA compliance based upon the velocities of the transmitral flow.

Transmitral flow profile can also help indicate the ventricle’s relaxation ability and LA pressure (LAP).

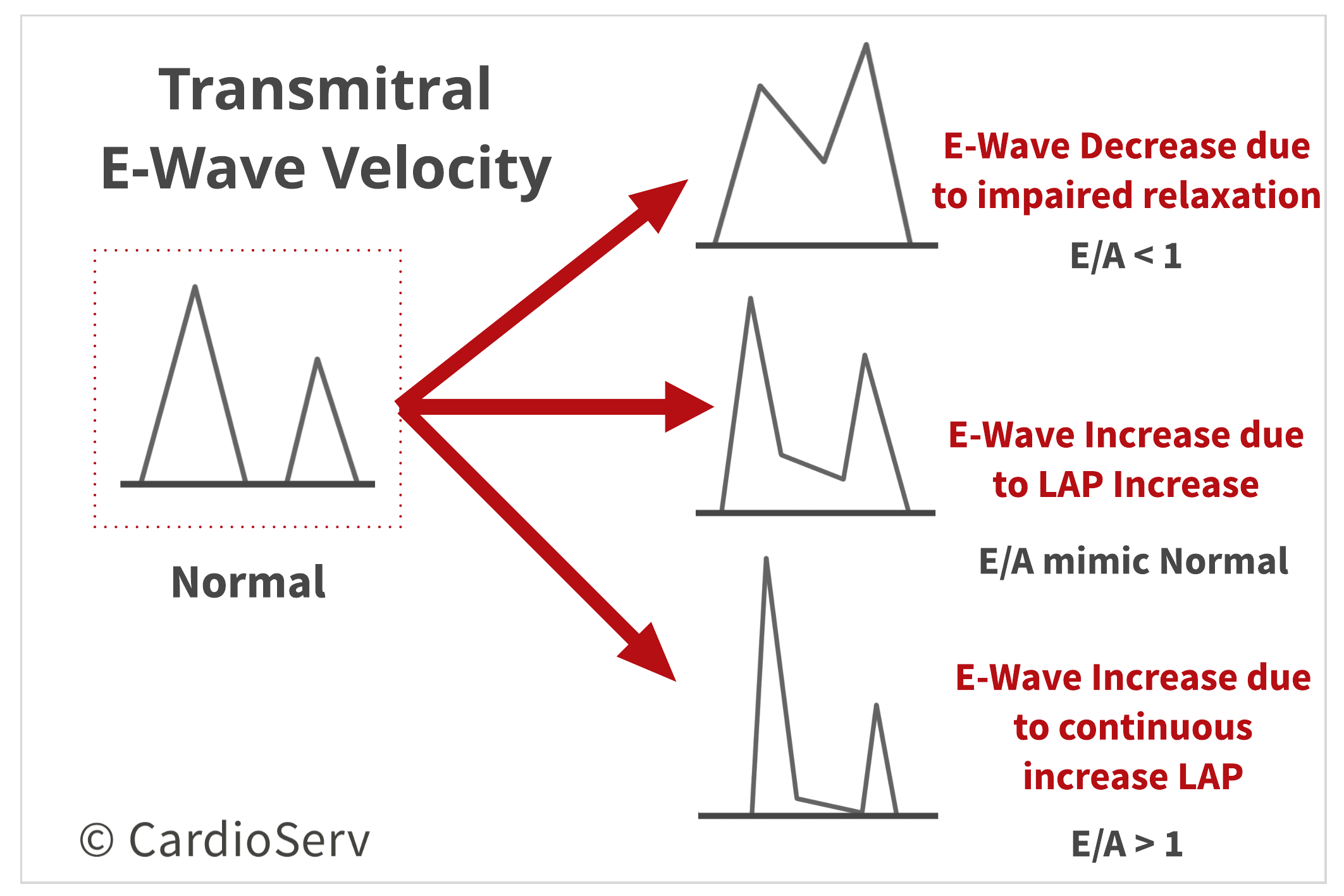

When the ventricle has prolonged or impaired relaxation, the E-wave velocity will decrease. In order for the heart to compensate for an abnormal relaxation, the LAP will increase. Once this occurs, the E-wave velocity will raise back, mimicking a normal velocity. The peak E-wave velocity is influenced on the LAP. Therefore, if the LAP is elevated, the E-wave velocity will increase causing a high E/A ratio (E/A > 1). This tells us that as the severity of diastolic dysfunction progresses, the decrease of LV relaxation and increase of LAP, having opposite effects on the transmitral E-wave velocity.

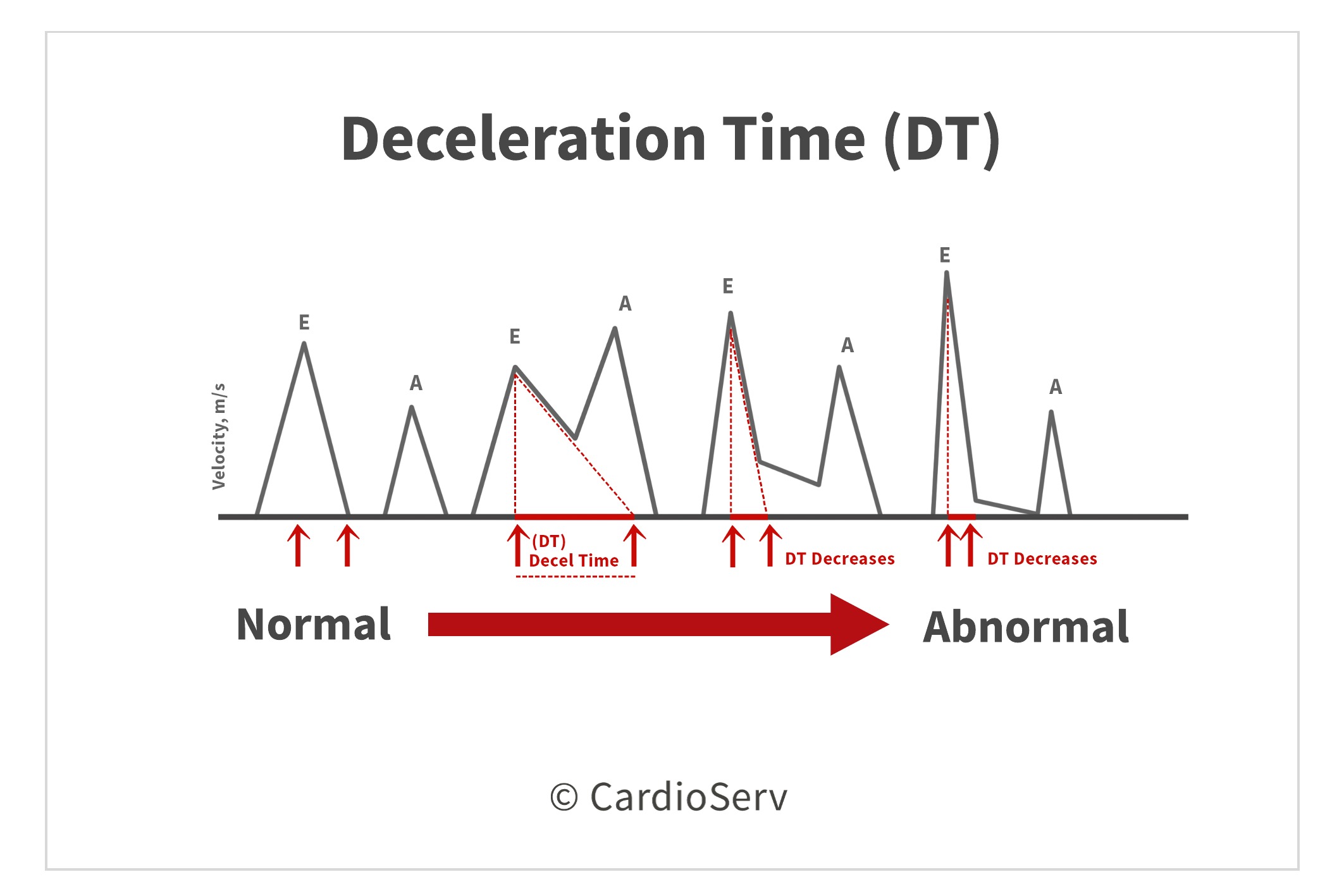

Another method to evaluating both relaxation and filling pressures is by the E-wave Deceleration Time (DT). There is a relationship between the compliance of the LV (how well it relaxes) and DT. If the ventricle has a prolonged or impaired relaxation, the DT duration will be long. When the ventricle experiences elevated filling pressures (increased LAP), the DT duration will be short.

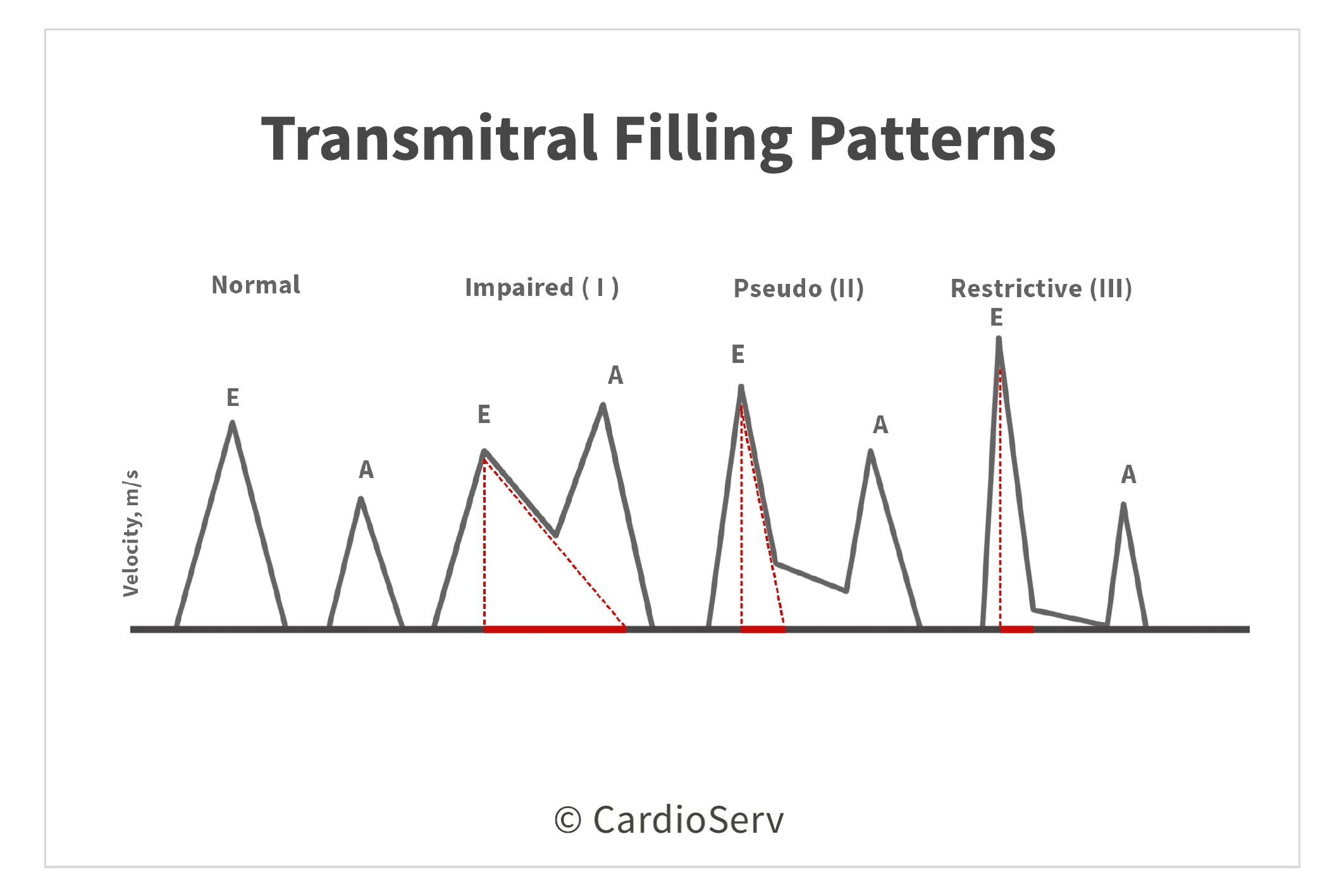

The transmitral flow can also provide us information on the progression of diastolic dysfunction by using the flow patterns to grade the severity. It is vital to understand the transmitral filling patterns are preload dependent! Being preload dependent helps determine if there are reversible loading conditions, for example patients with end stage renal disease on dialysis. This is also why we use other parameters in combination with transmitral flow to evaluate diastolic function.

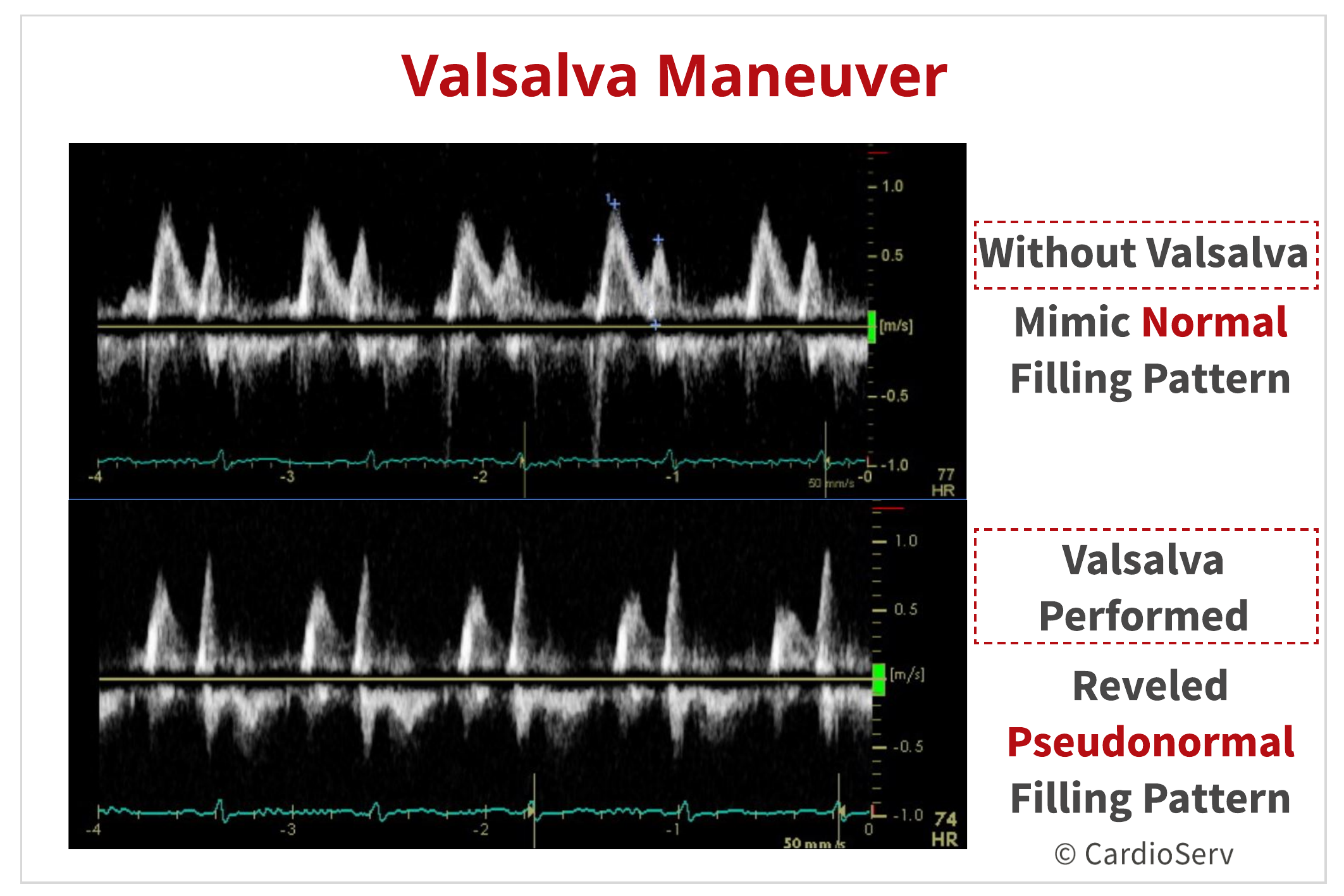

The Valsalva maneuver allows us to alter the loading conditions by removing the compensatory effects that occur during our interrogation of transmitral flow. This helps us distinguish a normal filling pattern from a pseudonormal pattern and whether a restrictive pattern is reversible or not. A decrease in E/A ratio by > 50% is supportive of diastolic dysfunction and highly specific for elevated filling pressures.

When the maneuver is performed, the patient should strain for 10 seconds while the sonographer obtains a continuous pulsed-wave Doppler recording of the transmitral flow. The displaying waveforms are dependent upon many factors, a few being:

A positive to being preload dependent is the ability to determine the presence of elevated intravascular volume, or if reversible results are obtainable by releasing pressure to allow a more compliant ventricle.

Next we are going to talk about how transmitral flow can alter the findings in the presence of diastolic dysfunction!

Andrea Fields MHA, RDCS

Andrea Fields MHA, RDCS

Stay Connected: LinkedIn, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram

References:

Gillebert, T. C., Pauw, M. D., & Timmermans, F. (2013). Echo-Doppler Assessment of Diastole: Flow, Function and Hemodynamics. Education in Heart, 99, 55-64. Retrieved November 20, 2017, from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/deda/8ed40076f7bbb1da2668d190d15af9947c2d.pdf.

Nagueh, S. F., MD, Smiseth, O. A., MD, & Appleton, C. P., MD. (2016). Recommendations for the Evaluation of Left Ventricular Diastolic Function by Echocardiography: An Update from the American Society of Echocardiography and European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. American Society of Echocardiography, 29(4), 277-314. Retrieved October 31, 2017, from http://asecho.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/2016_LVDiastolicFunction.pdf

Andersen, O. S., MD, Smiseth, O. A., MD, & Dokanish, H., MD. (2017). Estimating Left Ventricular Filling Pressures by Echocardiography. Journal of the American College of Cardiology,69(15), 1937-1948. Retrieved November 29, 2017.

Mitter, S. S., MD, Shah, S. J., MD, & Thomas, J. D., MD. (2017). A Test in Content: E/A and E/e’ to Assess Diastolic Dysfunction and LV Filling Pressures. Journal of the American College of Cardiology,69(11), 1451-1464. Retrieved November 29, 2017.

Mottram, P. M., & Marwick, T. H. (2005). Assessment of Diastolic Function: What the General Cardiologist Needs to Know. Heart British Cardiovascular Journal,91, 681-695. doi:10.1136

Jan

2018